Review of IAB SafeFrame 1.0

This review of the IAB SafeFrame 1.0 proposal has been prepared by Dr Simon Overell and Dr Douglas de Jager.

What are SafeFrames?

Currently there are two ways for a publisher to include display ads on a web page: inline or within iframes. This provides publishers with a stark choice.

By including an ad inline a publisher is including an ad in the same way that a publisher would typically include, say, an image. This type of inclusion provides advertisers with full transparency into where ads are placed and it also allows rich ad interactions—in particular, it allows expansion and contraction of ads. However, this type of inclusion also allows negligent or malicious advertisers to break site functionality; to steal data from the host page or from the user; to rewrite any content on the host page; or even to redirect a user to a page on an entirely different domain.

For the security-conscious publisher, iframes provide an impassable barrier between the host page and the ad. This protects both publishers and users from ad scripts. Unfortunately iframes also prevent rich interactions. More troublingly iframes limit what the ad can find out about the host page—for example, geometric position of the ad, whether the ad is viewable within the browser viewport, site metadata, site name, etc.

SafeFrames are an attempt to provide advertisers both with transparency and rich interactions whilst at the same time ensuring publisher and user security (and, indeed, advertiser security). External content is isolated on a trusted third party domain, thereby providing publishers the same protection as provided by traditional iframes. Communication between the host page and the external content is available via a defined API. This allows for rich ad interaction and it allows for certain information to be made available from the host page to the advertiser.

SafeFrames are of limited use across exchange inventory

The key advantage of SafeFrames is that they protect the publisher.

SafeFrames purport also to provide advertisers with increased transparency over standard iframes: including, for example, providing support for viewability classifications as per the 3MS standard and access to the cookies set under the host’s domain. However, it’s important for advertisers to realise that the data they are passed via SafeFrames is trustworthy only to the extent that the publishers are trustworthy. And across exchange inventory—across the long tail, in particular—advertisers would be advised to tread with caution. This is unfortunate as it’s across the long tail of exchange inventory where transparency is most wanted.

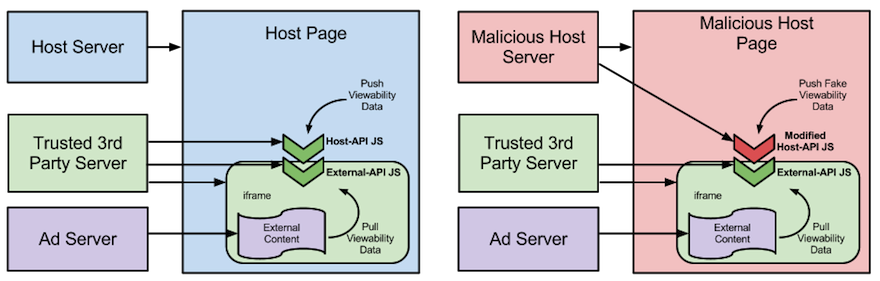

As the SafeFrame code is necessarily client-side, authenticating the validity of the messages passed from host page to an ad, via whichever API, is impossible. By modifying the SafeFrame JavaScript on the host site one can return false data to the advertiser.

This is illustrated below. It would be easy for a malicious site to feed fake viewability data into a modified host page. This would then be exposed in the iframe via the $sf.ext API. Any advertiser scripts pulling viewability data would receive fake rather than legitimate viewability classifications. If advertisers optimise their ad buying for viewability, they would be ripe for abuse by unscrupulous publishers who can grossly manipulate their figures. Similarly if publishers are paid only for viewable ads, this too is open to manipulation.

Frame nesting difficulties

Beyond trust, there are two other concerns which are perhaps worth highlighting. The first of these centres on frame nesting.

The SafeFrame Version 1.0 documentation states: “SafeFrame containers are always rendered in the top-level HTML document”. There are, however, legitimate reasons beyond the publisher’s control which make this impractical. For example, the LinkedIn and StumbleUpon toolbars place publisher web pages within iframes.

One might wonder whether the LinkedIn and StumbleUpon toolbars might switch to SafeFrames rather than iframes. Unfortunately, according to the SafeFrame Version 1.0 documentation: “Nested SafeFrame tags are not supported. Any SafeFrame tags that are included in tags from exchanges, intermediaries, proxies, or any other secondary publishing partner or vendor are ignored. If a SafeFrame tag is rendered within a SafeFrame container that has already been created, the rendering process assumes that the container has already been created and skips over to rendering the external content.” This would mean that if the StumbleUpon toolbar embedded the Yahoo! homepage in a SafeFrame, then any SafeFrames intended for ads on the Yahoo! homepage would be ignored and advertiser scripts would be able to rewrite the contents of the Yahoo! homepage.

This nesting difficulty significantly limits the applicability of SafeFrames. For example, a platform provider such as Facebook cannot encase their apps in SafeFrames and have their apps further include ads in SafeFrames.

Open-source but not necessarily free

A final point worth considering regarding SafeFrames is that even if an open-source implementation is released, the use of SafeFrames will not necessarily be free. comScore own a set of patents for measuring the viewability of display ads and comScore have recently shown a willingness to assert these patents in court. These patents specifically cover using geometric location of the ad to determine viewability—the method specified in the SafeFrames external API.

Concluding thoughts

The motivation behind SafeFrames is clear. Protection is needed by both publishers and advertisers from malicious or negligent parties. This is why iframes have come to be the predominant way to serve display ads. At the same time, advertisers require transparency and control on where and how their ads are displayed.

If all the different parties were diligent and their interests were aligned, SafeFrames would be a viable solution. In reality, however, SafeFrames protect only the publisher and they give the advertiser the illusion of transparency. Down the long tail of exchange inventory, where transparency is most needed by advertisers, this is where SafeFrames are least likely to help advertisers.

Compounding this intrinsic SafeFrame problem for advertisers are two structural difficulties. In today’s world, frame nesting is commonplace, and often required, and SafeFrames make no allowance for this nesting. Furthermore, unless comScore dramatically changes its policy on IP enforcement, users of SafeFrames for viewability measurement face the unwanted risk of being taken to court.